It was just a normal day when I found my mind wandering to the travails of a friend far away, who was probably going about his day as he usually does.

From a distance, I was recently privy to the everyday mountains he climbs to be independent. He is blind, you see. I’ve known him for years so you’d think this wouldn’t be a revelation but it was – mainly because I have always known him to be… well, independent.

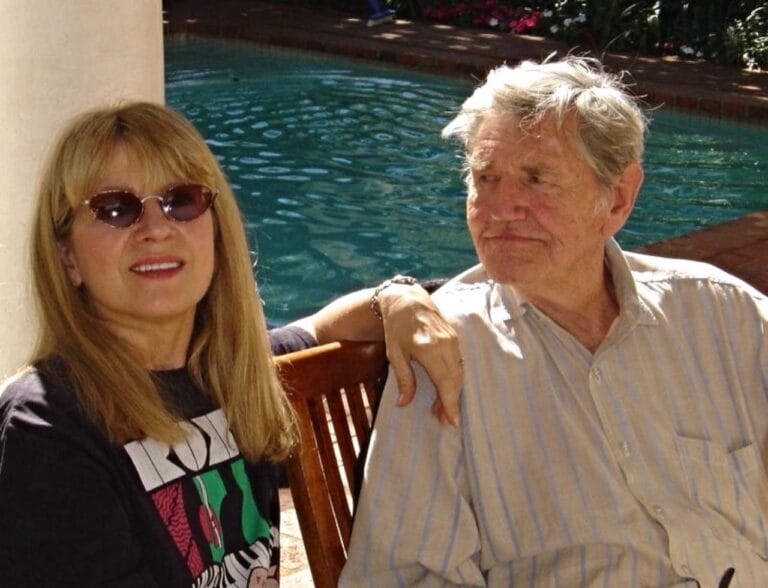

He is John Miller who has himself written on these pages.

Starting at the beginning of our friendship, briefly, he had a flat, a job and a white stick that he used to clear the way ahead. Those with the stomach for it watched his daily crossings of Commissioner Street, Johannesburg, as he made his way to the journalists’ pub; first, he took on the traffic and then a Porsche that parked on the pavement of the corner outside the local. It wasn’t an activity I warmed to but at least the car came off worse than he did. Everyone felt comfortable knowing “he could take care of himself”.

A couple of decades down the line, my friend lives in the U.K. Separated from a partner of 10 years, an amicable agreement saw him remain in their house – he thought in perpetuity – but a rude shock awaited him a couple of months ago.

His ex and her partner laid claim to the house to which he had contributed financially in its acquisition and where my friend felt at home. My philosophy of never taking sides fell by the way and in any case, I don’t know her. Now I reach the heart of the matter.

Distraught, not an emotion he has revealed to me before, he told me of the uphill of moving house as a blind person who is a relative stranger in his surroundings. On impulse, he took a house in a city some miles away – sight unseen, if you’ll forgive the description.

The timing was rash. The big move was marked down as over the Easter weekend – not exactly a time to make friends and influence them. Things a sighted person takes for granted are major obstacles. Not only would the layout be like a maze for some time to come but he needed a sighted person to point out safe plugs; changes in levels inside and out; kitchen appliances – are they electric? Or gas? And is there grass outside for his Jack Russel to excrete? As it turned out, there wasn’t, so where was the nearest place? Was it safe to walk his dog there and how many paces to and from his new home? Where was the bin for depositing the poo?

Not a minor undertaking, this last exercise entails FaceTiming a friend elsewhere in the U.K. Then, holding his iPhone in one hand, the poo bag in the other, he gets down on his hands and knees while his faraway friend directs him. It brings a whole new dimension, I thought, to the children’s game Pin the Tail on the Donkey.

Back to the anticipated move, he was still trying to solve his problems. He had tried all the organisations in the area – there were two societies for the blind nearby – neither could respond with the urgency he required. One told him they would send someone to assess him a few months hence and the other wasn’t worth mention.

I had a eureka moment, I thought, when I offered to contact a friend who is a Rotarian. He liked the idea but said I should leave it with him, he would contact a local branch. Online, he was asked to register to enter the site but he had to prove he wasn’t a robot with codes he couldn’t decipher. And they wanted a photograph – a selfie? It was my first smile during his uncharacteristic rant.

“WHAT!”, I could imagine him demanding as I recalled his FaceTime calls where I mostly talk to a corner of the room, or on a good day, an eye.

It was a momentary light moment for which I could depend on getting a laugh as – on a normal day – we share a sense of humour about personal foibles.

Luckily, two good Samaritans had been identified to help him move, but then he would be on his own for Easter – not before discovering, however, that the green curtains he ordered from Amazon for the kitchen were pink. “In the greater scheme…”, I ventured, but was cut short. “Absolutely not!”, he raged.

He had to pay the driver of the car but adding insult to injury, he found his Internet and telephone, which connected him to the world and which he had been promised would be functional, were not connected to WiFi yet, which meant among other things that he had no access to banking apps.

Trust plays a major role in the life of an “independent” blind person. He handed over his bank card and the password to his newfound BF, the driver, as he has done countless times to strangers before without incident.

This last anecdote made me think how many really good people there actually are in the world. Our perception of the human race is sadly coloured by the rotten crop.

I’m sure in time my friend will be familiar with his surroundings and his anger and frustration will have abated, but if this day in the life of a blind person on the move makes just one more person aware of the person with the white stick, it could make the world a friendlier place…