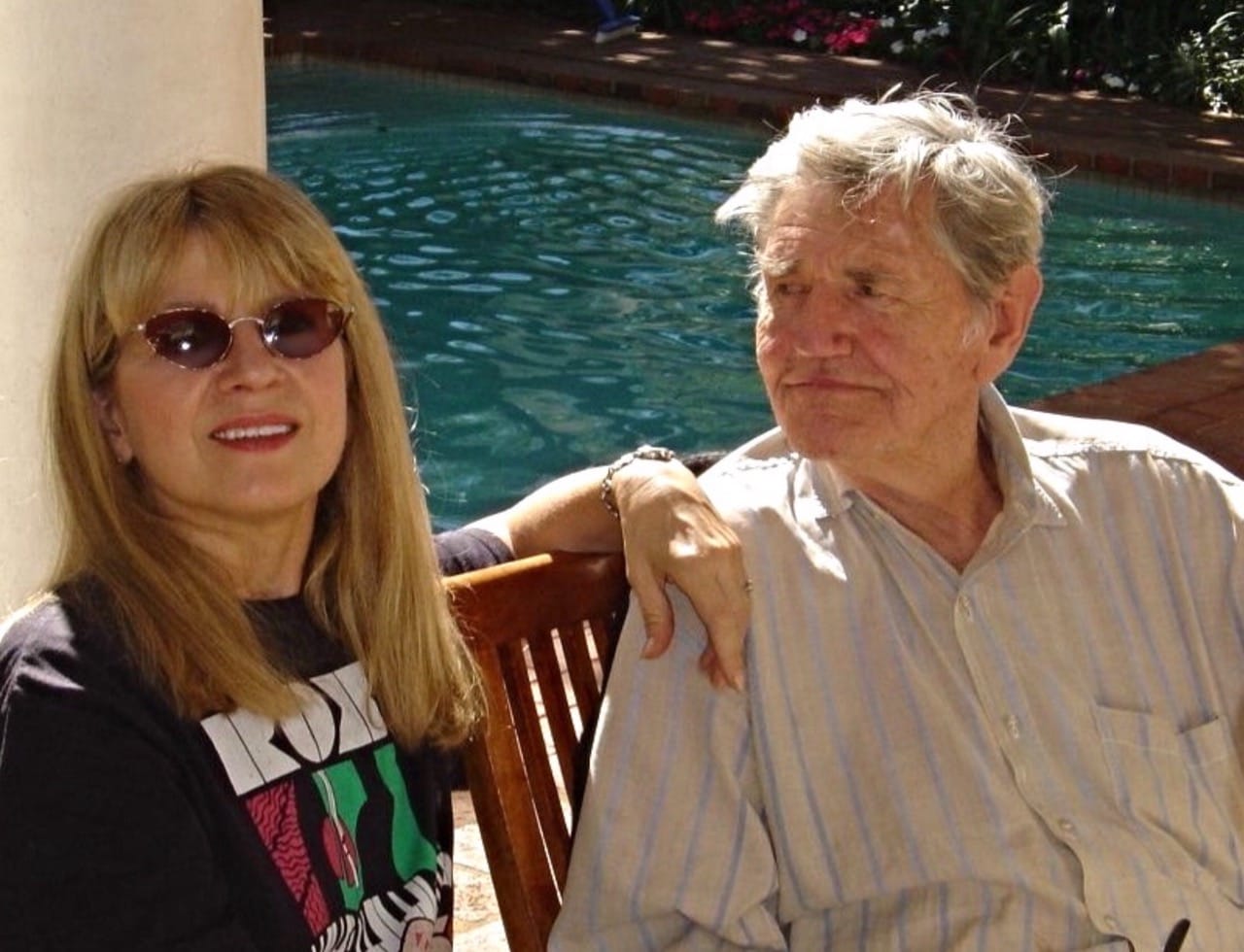

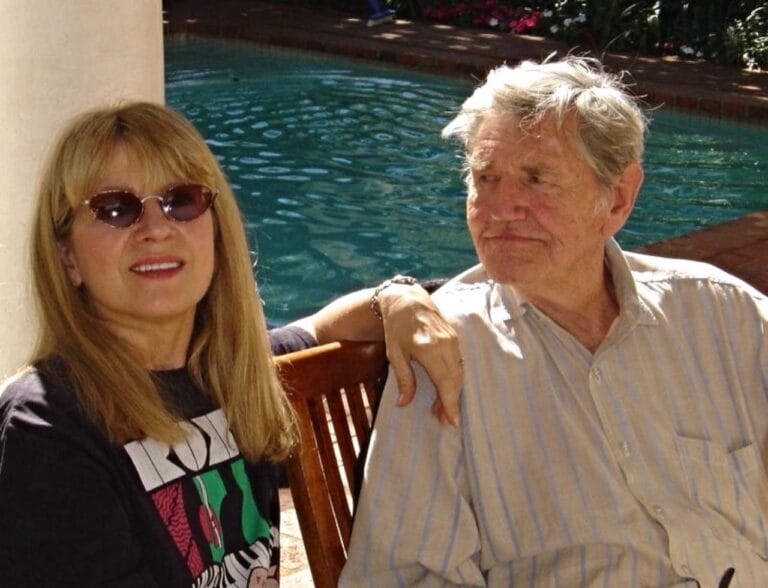

In 1996, Suzanne Brenner made a documentary about Robert Griffiths Hodgins, and other than its original television broadcasts on Arts Unlimited, it was barely seen by the public. After inadvertently destroying the last DVD copy she had, Suzanne decided it was time to post it on YouTube (watch below). It has already garnered comments like:

“Beautiful, Suzanne! A timepiece. You capture Robert’s endearingly gentle and quirky personality, and his fresh as ever paintings.”

– RoseLee Goldberg, Founder and Director of Performa, New York (and one-time student of Hodgins)

“This was the most unexpected and amazing treat. Thank you, dear Suzanne. You did something eternally wonderful.”

– Tessa Webber Goldin, Oxford“WHAT A TREAT. Utterly delightful. Thank you for putting this up.”

– Charles Anderson, Tunbridge Wells

Watch Video: Robert Hodgins Profile, Arts Unlimited, South Africa, 1996

Robert Griffiths Hodgins was a celebrated artist when he died in Johannesburg in 2010, just short of his 90th birthday. A lunch he had planned from his own culinary repertoire for the occasion went ahead without him and as a testament to his popularity, there wasn’t an empty seat.

Born in London in 1920 to a single mother who didn’t have the means to give him the education he deserved, Robert had an extremely hard childhood and was frequently left to his own devices. Cold and bare foot, he sought shelter in London’s Tate Gallery where some of the attendants took pity on him and allowed him to linger and even talked to him about paintings he liked. He often credited those times with igniting his passion for painting.

“It’s been said very often I’m a very English painter in the tradition of Freud and Bacon but where I really come from is an immense love and respect of the idea of art – of it carrying weight; of it carrying importance, of it carrying personal intensity. I don’t think I live more intensely than when I’m in front of a canvas,” Robert told Suzanne.

Neil Dundas (left), Research and Archive Consultant at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, is a respected authority on Robert’s work and applauded Suzanne’s decision to go public with the documentary. A close friend of the artist, Neil adds some observations.

“As a child in Depression-era London, Robert met ‘punch drunk’ retired boxers, beaten men who were gruffly kind to him, ladies of the night, dance hall girls and crooners; circus folk and ne’er-do-wells, who were later to become favourite subjects in his paintings,” says Neil.

Robert left school at 14 to work as a newspaper delivery boy, a life he escaped when his great-uncle, who owned Cape Town’s Harbour Café, invited him to South Africa in 1938. His great-uncle encouraged him to study for his matric, which he duly did, but his tertiary education would come later. When World War 11 broke out, Robert joined the Union Defence Forces and served his country in North Africa.

In 1945 he returned to England and his studies with a view to becoming a teacher but his plans took a turn for the better when he was accepted at the prestigious Goldsmith’s College of Art, and he pursued his first love.

On leaving Goldsmith’s he faced a tough time in London and returned to South Africa where he combined writing art criticism for News Check magazine and lecturing, first at Pretoria Technical College, and later at the University of Witwatersrand, where he continued teaching until 1983.

“Closing the door on his teaching career at Wits was liberating for Robert,” says Neil. “He flourished in his new freedom, which enabled him to focus on painting and learning new art techniques.

“His skilled and witty paintings examined petty bureaucrats or powerful men in suits and uniforms,” says Neil. “He was an acid social critic with a conscience, but also had a well-developed sense of the absurd.”