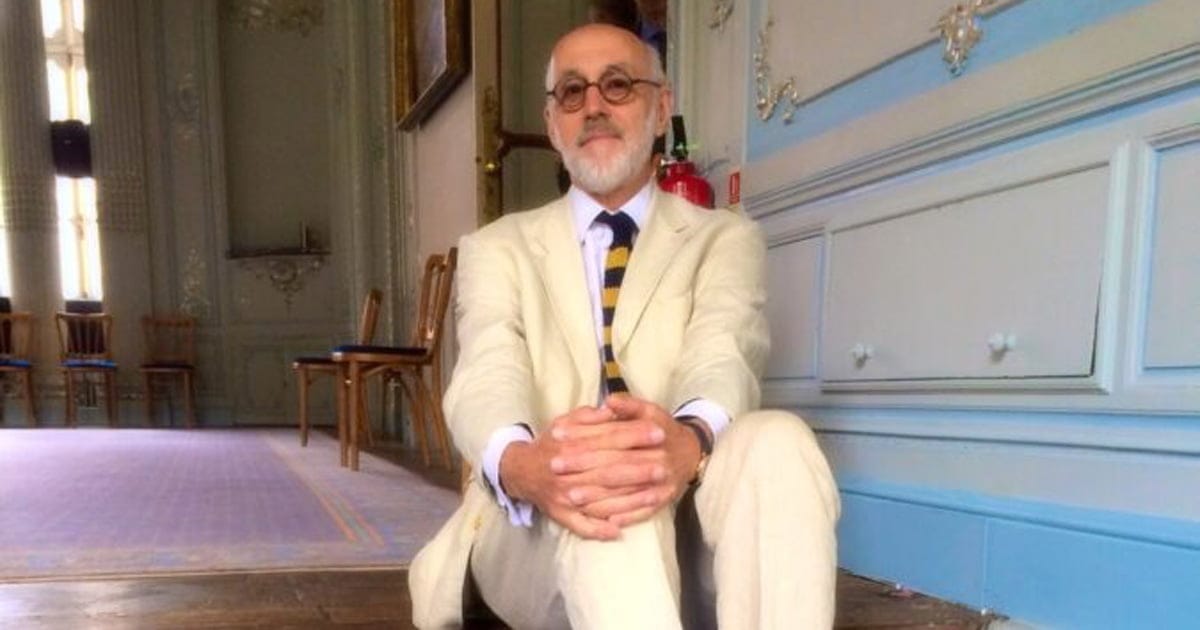

South African-born Norman Coates is a retired theatre designer who lives in London. He’s been making headlines in the art world about a secret erotic art collection that was for many years passed from safe keeper to safe keeper.

The explicit and exquisitely executed collection of 422 drawings is the work of a well-known, 20th Century British artist, Duncan Grant, a member of the Bloomsbury Group of English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists, who produced the body of work at a time when homosexuality (not to mention erotica) was illegal in Britain.

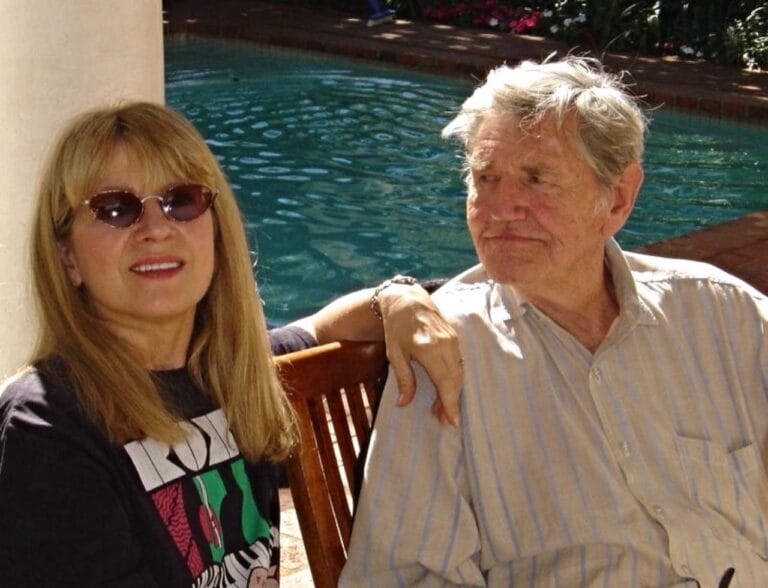

The last surviving person associated with the Bloomsbury Group to receive the drawings was Mattei Radev, Norman’s life partner. Before he died in 2009, he nominated Norman as next in line to protect the erotic artworks.

For 11 years, Norman hid them under his bed but a few years ago he decided the time was right to find them a home where they could, at last, be appreciated. They have been handed over to Darren Clarke, head of collections at Charleston, the Sussex farmhouse where Duncan Grant lived and worked.

When asked why now, Norman told the BBC: “They have been weighing heavily on my mind and I’ve been wondering who I might pass them on to and I thought this could go on for centuries if we don’t stop it.

“Duncan Grant has been gone a long time. The world has changed sufficiently and it feels right to put his work out there.”

The following interview was conducted with Norman Coates on BBC TV.

NORMAN’S BABY: THE THEATRE DOWNSTAIRS, CAPE TOWN

In the 1970s, Norman Coates asked me to start a theatre with him in Cape Town.

I was visiting my parents in Durban, on a brief visit from London, where I had made my home as a self-described “exile from apartheid”. Before leaving London – where I had attended a post-grad drama school – I phoned my friend, music promoter Bryan Miller, to tell him I would be away for a couple of weeks but as fate would have it, he was out the office and someone else took the call.

A long conversation ensued between musician Tony Osler and me and I learnt from him that Canticle – a music trio he was part of with Norman Coates and Mandi Wilson (later to change her name to Marloe Scott Wilson) – was about to tour South Africa with Daniel Boone. I thought no more of it.

In Durban, Dan Pienaar, a journalist friend and colleague of my eldest sister who had settled in London before me, popped in to greet my parents. Dan, who was Johnny Clegg’s stepfather, invited me for a meal. We didn’t like his first choice of restaurant, so we headed for the Edward Hotel, where there was a group performing cabaret. “I’m sure I spoke to one of those guys in London,” I told Dan.

At the end of their set, I went and introduced myself to Tony, Norman and Mandi. The four of us spent time together in Durban ahead of my intended return to London. Not very long after we met, Norman said I was just the person he was looking for to start a theatre with him in Cape Town. I was adamant that nothing would induce me to stay in South Africa.

Norman persisted and said I should at least come and take a look at Cape Town. Once there, we started scouting venues for a theatre and one thing led to another and we settled upon a tiny, intimate space beneath La Perla in Rondebosch, where the owner, Emiliano Sandri, agreed to accommodate us at no cost.

London would have to wait, I finally agreed, and I was ensconced in the Theatre Downstairs as the resident actress – with Alan Johns, a British actor, as my male counterpart. Not very long afterwards, Tony, the person who changed my destiny by answering Bryan Miller’s telephone, soon joined the line-up, replacing Alan.

We were an energetic threesome who found a niche in Cape Town. The Space Theatre, which had become a globally known entity for its anti-apartheid stance and excellent theatre, welcomed us as the new kids on the block and some of our shows were performed at the Space as well as the Theatre Downstairs. It was an exciting time.

And thus a long association with Norman Coates began…

To be continued…